Undesired Third Party Code Update: Impacts and Comparisons

Ty Ehuan, Political Science B.A. & Economics B.S., the university of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

The Duke-Media Trust partnership has continued to provide valuable information regarding the prevalence and impact of third-party code across the internet. A fellow member of the research team, Harrison Grant, has previously explored the broader privacy implications this undesired code presents, but in this post I limit the focus to provide an update on the data collected since the start of the year and what it means for the average internet user.

The research team from the Sanford School of Public Policy at Duke University and The Media Trust has continued to analyze two different datasets of synthetic profiles as they interact with the web, one appearing as they use the Duke University network and the other as they work from home. A further description of how these two datasets are gathered was explained in a previous blog post that can be found here. It is also key to note that the categories used to describe the third-party code has changed since this project began, a breakdown of these new naming conventions can be found here.

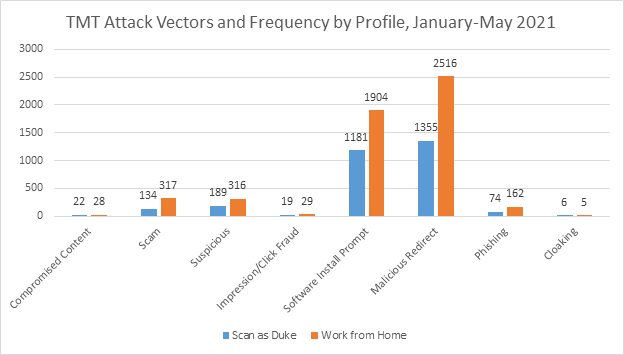

Now that the team has access to a much longer period of results we can begin to make a more informed comparison of the Duke and Work from Home datasets. From October 2020-May 2021 The Media Trust conducted 6,631,443 and 13,427,385 scans of the internet through each of these groups of profiles respectively. These scans are equivalent to an internet user visiting a unique page as they browse the web. Unsurprisingly this disparity in scan volume led the Work from Home profiles to encounter more malicious third-party code with a total of 10,960 incidents compared to the 5,911 incidents that the Duke profiles saw. A clear trend is mirrored among both datasets with malicious redirects and software install prompts representing over 80% of the incidents in both datasets.

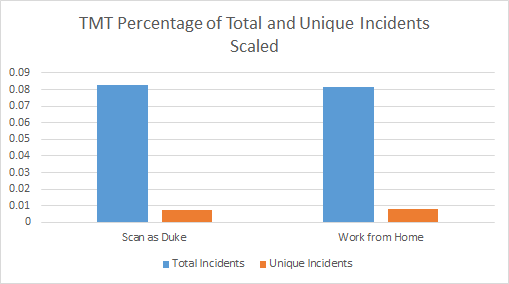

After scaling these numbers to the number of scans, we found that .0816% of the Work from Home scans encountered this undesired code compared to .0891% of the Duke scans. This means that on average The Media Trust found this potentially dangerous third-party code on every 1,225 and 1,122 scans of the internet respectively for the two datasets. Due to the sheer volume of scans conducted this is still a notable difference. but not one that is likely to affect the average internet user. However, for a large organization concerned about security liabilities this disparity could rapidly add up as all of its members use the web.

Based off of these results it would be easy to conclude that a large number of websites are compromised and represent security vulnerabilities, yet this is not the case. Many of the incidents originate from the same vector as it continually uses a vulnerability in the advertising ecosystem to attack web users. A single website could be responsible for over 100 separate attacks and until the malicious third party code was removed it would continue attempting to compromise the user. In fact, when we separated out only unique incidents and scaled them to the volume of scans we found that the Work from Home dataset actually showed 18.03% more unique attacks than the Duke dataset. We cannot say with any certainty why remote worker profiles would be targeted by unique attacks more than profiles associated with Duke University while the total number of attacks represents the opposite, but further research into this discrepancy could reveal some fascinating conclusions about malware in the advertising ecosystem.

These findings provide an interesting view into how malicious third-party code operates across the internet. However, one important piece of context that has yet to be discussed is what this means for the average user. There is no conclusive data on how many webpages the average internet user interacts with, but estimates place this number between 100-150 a day. Based off of the number of attacks discussed above this means a remote worker would be served with malicious code every 8 to 12 days. For the majority of users this might simply mean an annoying ad that is easily spotted as malware, but it could also mean they interact with a sophisticated attack that slips past their guard. And if said user has access to important company data they could quickly expose their employer to a breach or ransomware attack.

Third-party code creates a variety of security risks for individual users and businesses. These range from simple privacy violations to insidious attacks that threaten sabotage to extort entities for money. If attacks target critical infrastructure such as a hospital this danger becomes life threatening making their prevention imperative. Going forward we will continue to explore how these vulnerabilities are exploited in the advertising ecosystem, who they target, and the remedies most likely to protect from these kinds of attacks.